Advanced¶

The basic interface explained in the Introduction should provide you enough to start detecting communities. However, perhaps you want to improve the partitions further or want to do some more advanced analysis. In this section, we will explain this in more detail.

Optimiser¶

Although the package provides simple access to the function

find_partition(), there is actually an underlying

Optimiser class that is doing the actual work. We can also

explicitly construct an Optimiser object:

>>> optimiser = la.Optimiser()

The function find_partition() then does nothing else then

calling optimise_partition() on the provided

partition.

>>> diff = optimiser.optimise_partition(partition)

optimise_partition() simply tries to improve any

provided partition. We can thus try to repeatedly call

optimise_partition() to keep on improving the current

partition:

>>> G = ig.Graph.Erdos_Renyi(100, p=5./100)

>>> partition = la.ModularityVertexPartition(G)

>>> diff = 1

>>> while diff > 0:

... diff = optimiser.optimise_partition(partition)

Even if a call to optimise_partition() did not improve

the current partition, it is still possible that a next call will improve the

partition. Of course, if the current partition is already optimal, this will

never happen, but it is not possible to decide whether a partition is optimal.

This functionality of repeating multiple iterations is actually already built-in. You can simply call

>>> diff = optimiser.optimise_partition(partition, n_iterations=10)

If n_iterations < 0 the optimiser continues iterating until it encounters

an iterations that did not improve the partition.

The optimise_partition() itself is built on two other

basic algorithms: move_nodes() and

merge_nodes(). You can also call these functions

yourself. For example:

>>> diff = optimiser.move_nodes(partition)

or

>>> diff = optimiser.merge_nodes(partition)

The simpler Louvain algorithm aggregates the partition and repeats the

move_nodes() on the aggregated partition. We can easily

emulate that:

>>> partition = la.ModularityVertexPartition(G)

>>> while optimiser.move_nodes(partition) > 0:

... partition = partition.aggregate_partition()

This summarises the whole Louvain algorithm in just three lines of code.

Although this finds the final aggregate partition, it leaves unclear the actual

partition on the level of the individual nodes. In order to do that, we need to

update the membership based on the aggregate partition, for which we use the

function

from_coarse_partition().

>>> partition = la.ModularityVertexPartition(G)

>>> partition_agg = partition.aggregate_partition()

>>> while optimiser.move_nodes(partition_agg) > 0:

... partition.from_coarse_partition(partition_agg)

... partition_agg = partition_agg.aggregate_partition()

Now partition_agg contains the aggregate partition and partition

contains the actual partition of the original graph G. Of course,

partition_agg.quality() == partition.quality() (save some rounding).

Instead of move_nodes(), you could also use

merge_nodes(). These functions depend on choosing

particular alternative communities: the documentation of the functions provides

more detail.

One possibility is that rather than aggregating the partition based on the

current partition, you can first refine the partition and then aggregate it.

This is what is done in the Leiden algorithm, and can be done using the functions

move_nodes_constrained() and

merge_nodes_constrained(). Implementing this, you

end up with the following high-level implementation of the Leiden algorithm:

>>> # Set initial partition

>>> partition = la.ModularityVertexPartition(G)

>>> refined_partition = la.ModularityVertexPartition(G)

>>> partition_agg = refined_partition.aggregate_partition()

>>>

>>> while optimiser.move_nodes(partition_agg):

...

... # Get individual membership for partition

... partition.from_coarse_partition(partition_agg, refined_partition.membership)

...

... # Refine partition

... refined_partition = la.ModularityVertexPartition(G)

... optimiser.merge_nodes_constrained(refined_partition, partition)

...

... # Define aggregate partition on refined partition

... partition_agg = refined_partition.aggregate_partition()

...

... # But use membership of actual partition

... aggregate_membership = [None] * len(refined_partition)

... for i in range(G.vcount()):

... aggregate_membership[refined_partition.membership[i]] = partition.membership[i]

... partition_agg.set_membership(aggregate_membership)

These functions in turn rely on two key functions of the partition:

diff_move() and

move_node(). The first

calculates the difference when moving a node, and the latter actually moves the

node, and updates all necessary internal administration. The

move_nodes() then does something as follows

>>> for v in G.vs:

... best_comm = max(range(len(partition)),

... key=lambda c: partition.diff_move(v.index, c))

... partition.move_node(v.index, best_comm)

The actual implementation is more complicated, but this gives the general idea.

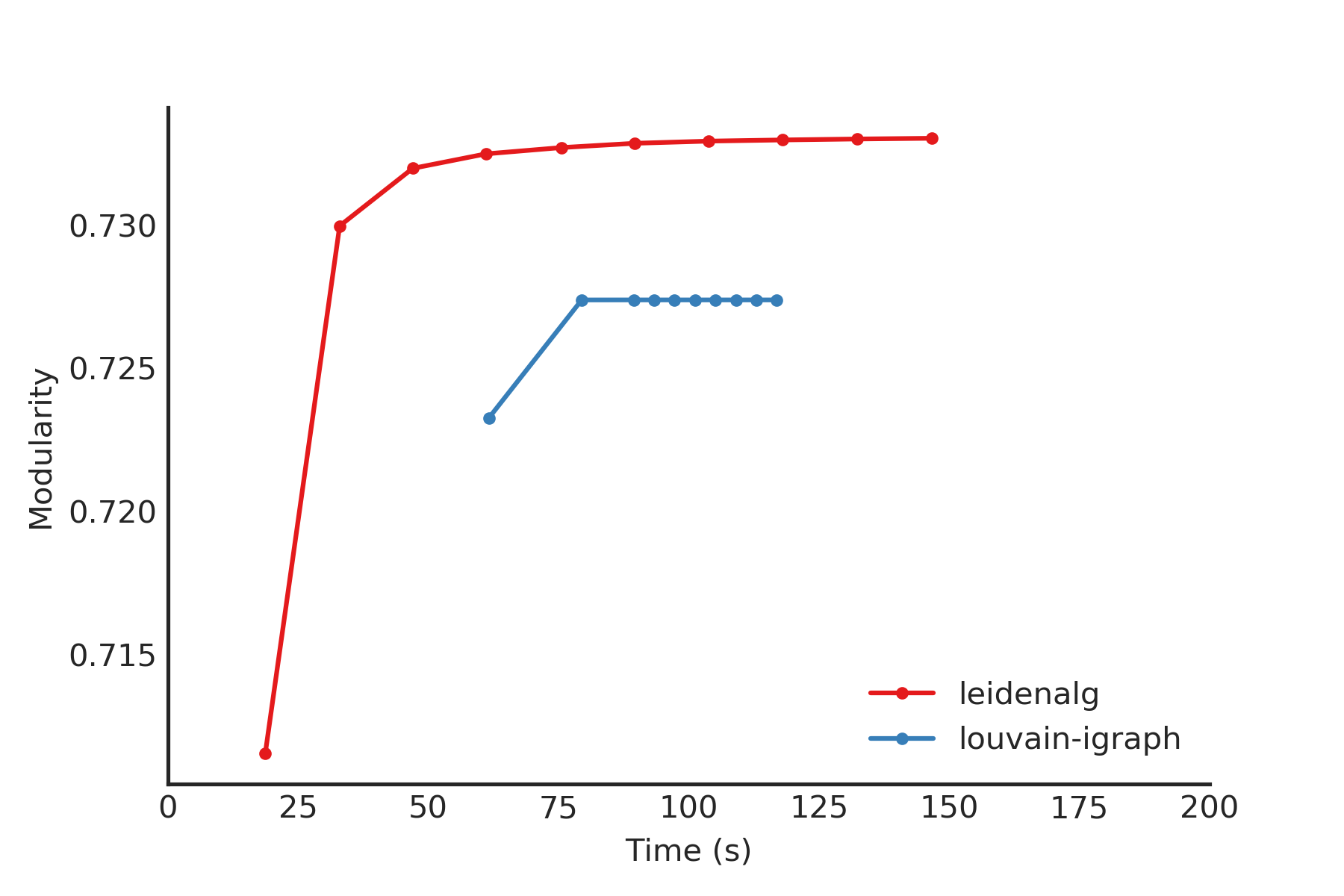

This package builds on a previous implementation of the Louvain algorithm in

louvain-igraph. To illustrate

the difference between louvain-igraph and leidenalg, we ran both

algorithms for 10 iterations on a Youtube network of more than 1 million

nodes and almost 3 million edges.

The results are quite clear: Leiden is able to achieve a higher modularity in less time. It also points out that it is usually a good idea to run Leiden for at least two iterations; this is also the default setting.

Note that even if the Leiden algorithm did not find any improvement in this iteration, it is always possible that it will find some improvement in the next iteration.

Resolution profile¶

Some methods accept so-called resolution parameters, such as

CPMVertexPartition or

RBConfigurationVertexPartition. Although some methods may seem

to have some ‘natural’ resolution, in reality this is often quite arbitrary.

However, the methods implemented here (which depend in a linear way on

resolution parameters) allow for an effective scanning of a full range for the

resolution parameter. In particular, these methods somehow can be formulated as

\(Q = E - \gamma N\) where \(E\) and \(N\) are some other

quantities. In the case for CPMVertexPartition for example,

\(E = \sum_c m_c\) is the number of internal edges and \(N = \sum_c

\binom{n_c}{2}\) is the sum of the internal possible edges. The essential

insight for these formulations [1] is that if there is an optimal partition

for both \(\gamma_1\) and \(\gamma_2\) then the partition is also

optimal for all \(\gamma_1 \leq \gamma \leq \gamma_2\).

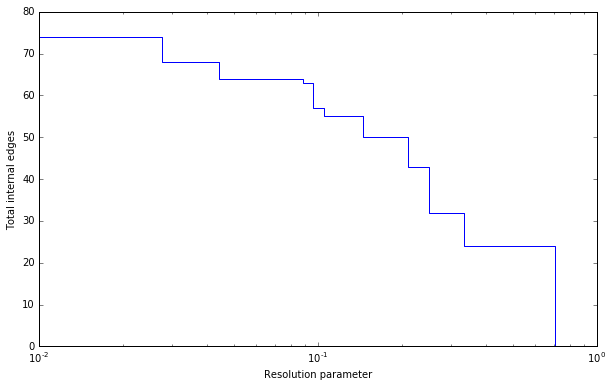

Such a resolution profile can be constructed using the

Optimiser object.

>>> G = ig.Graph.Famous('Zachary')

>>> optimiser = la.Optimiser()

>>> profile = optimiser.resolution_profile(G, la.CPMVertexPartition,

... resolution_range=(0,1))

Plotting the resolution parameter versus the total number of internal edges we thus obtain something as follows:

Now profile contains a list of partitions of the specified type

(CPMVertexPartition in this case) for

resolution parameters at which there was a change. In particular,

profile[i] should be better until profile[i+1], or stated otherwise for

any resolution parameter between profile[i].resolution_parameter and

profile[i+1].resolution_parameter the partition at position i should be

better. Of course, there will be some variations because

optimise_partition() will find partitions of varying

quality. The change points can then also vary for different runs.

This function repeatedly calls optimise_partition()

and can therefore require a lot of time. Especially for resolution parameters

right around a change point there may be many possible partitions, thus

requiring a lot of runs.

Fixed nodes¶

For some purposes, it might be beneficial to only update part of a partition.

For example, perhaps we previously already ran the Leiden algorithm on some

dataset, and did some analysis on the resulting partition. If we then gather new

data, and in particular new nodes, it might be useful to keep the previous

community assignments fixed, while only updating the community assignments for

the new nodes. This can be done using the is_membership_fixed argument of

find_partition(), see [2] for some details.

For example, suppose we previously detected partition for graph G, which

was extended to graph G2. Assuming that the previously exiting nodes are

identical, we could create a new partition by doing

>>> new_membership = list(range(G2.vcount()))

... new_membership[:G.vcount()] = partition.membership

We can then only update the community assignments for the new nodes as follows

>>> new_partition = la.CPMVertexPartition(G2, new_membership,

... resolution_parameter=partition.resolution_parameter)

... is_membership_fixed = [i < G.vcount() for i in range(G2.vcount())]

>>> diff = optimiser.optimise_partition(new_partition, is_membership_fixed=is_membership_fixed)

In this example we used CPMVertexPartition. but any other

VertexPartition would work as well.

Maximum community size¶

In some cases, you may want to restrict the community sizes. It is possible to indicate this

by setting the max_comm_size parameter so that this constraint is

taken into account during optimisation. In addition, it is possible to pass this parameter

directly when using find_partition(). For example

>>> partition = la.find_partition(G, la.ModularityVertexPartition, max_comm_size=10)